I want to share a pattern I’ve landed on over the years that has saved more than a few commissioning headaches. It’s about handling the reasons a sequence cannot start before you even try starting it, and doing so in a way operators actually understand.

If you’ve ever watched someone press Start on an HMI over and over with no clue why nothing happens, you know exactly why this matters. This isn’t scary or safety-critical logic. It’s practical readability and operability in the real world.

What Pre-Sequence Issue Handling Actually Is

At its heart, pre-sequence issue handling is fairly simple. Before letting a sequence run, you check everything that needs to be right. Not just is everything healthy, but is everything in the correct condition, and is there enough information here for a human to understand what went wrong.

Most systems I see lump these checks into the sequence itself. That works fine until it doesn’t, usually once the project grows and logic starts getting duplicated or scattered across steps. At that point, neither operators nor engineers can easily tell what is actually blocking execution.

I treat readiness evaluation as its own concern. A central logic block, or a small set of blocks, whose only job is to answer a simple question: from a logic point of view, do we have the conditions necessary to start?

This logic doesn’t start anything. It doesn’t care why you pressed Start. It just evaluates whether starting would be valid right now.

Why This Matters in Practice

Early in a project it’s tempting to embed checks everywhere. If this valve isn’t in auto, don’t start. If this instrument is faulted, don’t start. That approach works initially, but it scales badly.

Over time you end up with checks inside sequences, checks inside device blocks, and subtle differences in behaviour depending on where the check lives. That inconsistency is exactly what leads to operators hammering the reset button because they can’t tell whether the system is genuinely blocked or just being awkward.

Once readiness is treated as a separate evaluative layer, things become much clearer. Sequences become simpler. Changes are easier to reason about. Most importantly, there’s a single place to look when something won’t start.

The sequence itself only needs one answer: allowed or not allowed. All of the reasoning behind that answer lives elsewhere.

Building a Readable Exception Structure

The approach relies on consistency. Every check follows the same pattern: is the exception enabled for this particular check, has the operator requested a reset, is the device in the correct mode, is the device healthy, and what exception flags result from those conditions.

This is deliberate repetition. When you need to add a new check, you already know where it goes and how it should look. An iteration counter steps through each evaluation, building up a collection of individual exception states. These get aggregated later, but crucially, they remain individually addressable throughout.

That’s the difference between a system that explains itself and one that just says “not ready”.

Keeping the Reason Visible

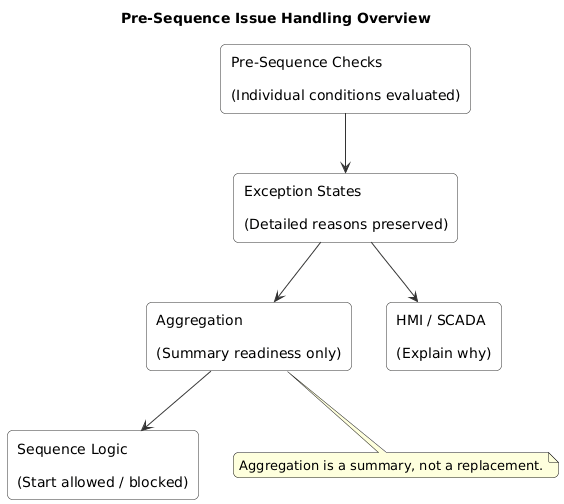

If the output of your pre-sequence logic is only a single ready or not ready bit, you’ve already lost the most important information: the reason.

Whenever a system isn’t ready, there’s always a reason, and often several. Collapsing all of that into one Boolean might be convenient for logic, but it’s a terrible interface for humans.

Let each condition fail independently. Each unavailable device, active interlock, missing feedback, or conflicting operation raises its own issue state. Those issue states can then be aggregated for control logic purposes without losing their individual meaning.

The key mistake many systems make is aggregating too early. By the time the HMI sees anything, all context has already been stripped away. Each exception needs its own flag and its own text reference before anything gets combined. The aggregation happens, but it happens late, after all the detail has been preserved.

Patterns Matter More Than Equipment

One of the useful realisations with pre-sequence handling is that the specific equipment doesn’t matter nearly as much as the pattern.

Whether you’re checking a valve, a pump, or an instrument, the questions are usually the same. Is it enabled. Is it in the correct mode. Is it healthy. Is it blocked by something else.

When these questions are asked consistently, behaviour becomes predictable. Engineers know where to add logic. Operators learn what unavailable actually means in practice. Documentation becomes easier because behaviour is no longer bespoke.

The checks for valves, pumps, and instruments all use the same evaluation structure. The parameters change, but the logic doesn’t. That consistency is what lets you scale to 50 or 100 checks without the system becoming unmaintainable.

A system with fewer checks but consistent behaviour is often more usable than a system with exhaustive logic applied inconsistently.

Handling Configuration-Dependent Checks

Not all equipment is always relevant. Some checks only apply when certain features are enabled. A heater might be optional. A steam valve might not be installed. A particular tank might not be in use.

Pre-sequence logic handles this well. Rather than duplicating configuration checks throughout the sequences themselves, they live in one place. If you disable a piece of equipment, all the related pre-sequence checks automatically drop out. The sequences don’t need to know. The operators don’t see irrelevant messages. The system just gets simpler.

This also handles the case where different operational modes need different checks. Backflush systems might have different suction tank sources, different flow meter requirements, different pressure constraints depending on configuration. All of that gets evaluated centrally, and the resulting exception flags tell each sequence what it needs to know.

Aggregation Without Going Silent

At some point, all those individual issue states do need to be combined. A sequence cannot reason about twenty separate flags.

The trick is to aggregate without becoming silent. High-level readiness outputs exist for the benefit of the PLC logic. They answer the question “can I start” quickly and unambiguously. They should never be the only thing exposed.

The individual exception arrays get converted to summary flags, then those flags block the sequences. But the individual exception states remain available for the HMI, for diagnostics, for troubleshooting.

A useful mental model is that aggregation provides a summary, not a replacement. The summary blocks execution. The detail explains why.

Reset Should Mean Re-Check

Reset behaviour is another subtle but important design choice.

Pre-sequence issues aren’t traditional faults, and treating them as latched alarms often causes confusion. If a condition is still invalid, resetting shouldn’t magically make the system ready. It should simply acknowledge the issue and allow the logic to evaluate again.

The exception reset signal gets pulsed and then distributed to every check. This doesn’t clear anything that’s still true. It just tells the logic to stop holding onto stale states and look at the current conditions again.

When reset is treated as a re-evaluation trigger rather than a force clear, operators quickly learn to trust the system. They stop repeatedly pressing reset and start addressing the underlying cause instead.

That trust is fragile, and once it’s gone, it’s very difficult to get back.

Where SCADA Text Management Really Helps

This is where PLC structure and SCADA design meet.

If every unmet pre-condition becomes a traditional alarm, the alarm list fills up with messages that aren’t faults and don’t require urgent action. Operators start ignoring alarms altogether, which defeats the point of having them.

A cleaner approach is to present pre-sequence issues as contextual messages rather than faults. In WinCC this often means generating text entries and associating them with an appropriate alarm class, without treating them as high-severity alarms.

Each exception gets a text reference, but those references don’t generate screaming red alarms. They populate a status display that operators look at before starting a sequence, not during an emergency.

This allows the system to explain itself without shouting. Operators see clear reasons why a sequence cannot start, while genuine faults retain their importance. Alarm classes stop being just about severity and start carrying meaning.

What Good Pre-Sequence Handling Feels Like

When this approach is implemented properly, the effect is subtle but noticeable.

Sequences start less frequently with immediate faults because operators can see problems before they try to run. Commissioning becomes calmer because issues present themselves clearly instead of appearing halfway through execution. Support calls shift from vague complaints to specific, actionable observations.

Perhaps most telling of all, engineers get fewer questions asking them to explain the system, because the system has learned to explain itself.

The logic is just organised. It checks devices, it checks interlocks, it checks operational states, and it presents all of that in a way that doesn’t require an engineering degree to interpret. That’s the goal.

Practical Implementation Details

The mechanics of this approach don’t require anything exotic. A dedicated function block handles the evaluation. Each network inside that block checks one condition using a standardised function call. An array tracks which exceptions are active. A few networks at the end aggregate those arrays into summary flags.

The function call itself is straightforward: enabled state, reset command, device mode, device health, resulting exception flags. Same inputs, same outputs, every time. When you write the tenth check, it looks identical to the first. When you come back six months later, you recognise the pattern immediately.

You can implement this with a single large block or split it across multiple smaller ones depending on system complexity. The principle remains the same: centralised evaluation, preserved detail, consistent patterns.

The Hidden Benefit: Commissioning and Troubleshooting

This approach really pays off when things go wrong, or when you’re bringing a system online for the first time.

During commissioning, you’re constantly tweaking device configurations, adjusting interlocks, enabling and disabling features. With pre-sequence checks scattered throughout the application, every change becomes a hunt. Did I update all the places this valve gets checked? Are there still references to equipment I disabled?

With centralised exception management, you change it once. The sequences don’t care. The HMI updates automatically. The operator sees the right messages immediately.

The same applies to troubleshooting. When an operator reports “the clean sequence won’t start”, you know exactly where to look. One function block, one set of exception flags, one place where all the logic lives. No hunting through sequence steps trying to work out which embedded check is causing the problem.

Avoiding Common Mistakes

There are a few traps I’ve seen people fall into when implementing this pattern.

The first is trying to make the exception logic too clever. Complex nested conditions, multiple levels of aggregation, dependencies between checks. It sounds sophisticated, but it becomes unmaintainable fast. The strength of this approach is its simplicity. Each check stands alone. The aggregation is trivial. Keep it that way.

The second mistake is treating every operational state as an exception. Not everything needs to block a sequence. Some conditions are just status information. Some are warnings. Some are reminders. Exception logic should answer one question: is it safe and sensible to start right now? If the answer is “yes, but you should know that…”, that’s not an exception, that’s just information.

The third trap is over-indexing on elimination of all false starts. You could write logic that checks every conceivable condition and never lets a sequence start unless everything is perfect. But that makes the system frustrating to operate. Sometimes the right answer is to let the sequence attempt to run and handle the problem during execution. Pre-sequence logic should catch the obvious problems, not prevent all possible failures.

Why This Works Long-Term

The real test of any control system pattern is how well it holds up two years later when someone who didn’t write the original code needs to modify it.

Pre-sequence exception management passes that test because it’s boring. There’s no clever trick to remember. There’s no architectural decision that made sense at the time but confuses people later. It’s just a list of checks that all look the same.

When a new engineer joins the project, they understand it immediately. When a feature gets added, they know where the new checks go. When something breaks, they know where to look. That predictability has value that’s hard to quantify but impossible to ignore once you’ve experienced the alternative.

Final Thoughts

Pre-sequence issue handling organises the logic you already have so that it reflects how people actually think about readiness.

When readiness is evaluated centrally, reasons are preserved, and messages are presented clearly through SCADA, the control system becomes easier to operate, easier to maintain, and easier to extend.

That’s a small architectural decision with long-term consequences, and one that’s well worth getting right. The pattern scales. The behaviour remains predictable. And when something doesn’t work, everyone can see why.